Last week Wally Ishibashi and I gave a presentation to the Hawaii County Council. There’s a video of our talk up now on local channel 52, where it will repeat from time to time.

Wally spoke about the Geothermal Working Group Report we gave to the legislature. I talked about “Peak Oil in the Rear View Mirror,” from the perspective of having been the only person from Hawai‘i to attend four Peak Oil conferences.

On Monday, I gave an essay presentation to the Social Science Association of Hawai‘i, whose members are prominent members of our community. This organization has been in operation since the 1800s.

From Kamehameha School Archives, 1886 January 21 -1892. Bishop becomes a member of the Social Science Association of Honolulu. All Bishop Estate Trustees and the first principal of Kamehameha Schools, William B. Oleson, are members. Members meet monthly to discuss topics concerning the well-being of society.

And yesterday I gave a “Peak Oil in the Rear View Mirror” presentation to the Office of Hawaiian Affairs’ Beneficiary Advocacy and Empowerment (BAE) Committee.

I was interested to note that the Hawaii County Council, the Social Science Association of Hawaii and OHA’s BAE committee were all overwhelmingly in favor of stabilizing electricity rates. It was clear to everyone that we in Hawai‘i are extremely vulnerable, and also so lucky to have a game-changing alternative.

Hawaii is the world’s most remote population in excess of 500,000 people. Almost everybody and everything that comes to Hawaii comes via ship or airplane using oil as fuel. As isolated as we are, we are vulnerable to the changing nature of oil supply and demand. There is trouble in paradise.

I explained how it was that a banana farmer came to be standing in front of them giving a presentation about energy.

My story started way back when I was 10 years old. I remember Pop talking about impossible situations, and suddenly he would pound the dinner table with his fist, the dishes would bounce, and he would point in the air. “Not no can, CAN!” And at other times: “Get thousand reasons why no can, I only looking for the one reason why can.” He would say, “For every problem, find three solutions …. And then find one more just in case.”

Once he said, “Earthquake coming. You can hear it and see the trees whipping back and forth and see the ground rippling.” He gave a hint: “If you are in the air you won’t fall down. What you going do?”

I said, “Jump in the air.” He said yes, and do a half turn. I asked why.

He said, “Because after a couple of jumps you see everything.”

Lots of lessons in what he told a 10-year-old kid. Nothing is impossible. Plan in advance.

I made my way through high school and applied to the University of Hawai‘i. But I came from small town Hilo, and there were too many places to go, people to see and beers to drink. I flunked out of school.

It was during the Vietnam era, and if you flunked out of school you were drafted. Making the best of the situation, I applied for Officers Candidate School and volunteered to go to Vietnam.

I found myself in the jungle with a hundred other soldiers. It was apparent that if we got in trouble, no one was close enough to help us. The unwritten rule we lived by was that “We all come back, or no one comes back.” I liked that idea and have kept it ever since.

I returned to Hawai‘i and reentered the UH. I wanted to go into business, so I majored in accounting in order to keep score.

Pop asked if I would come and run the family chicken farm. I did, and soon realized that there would be an opportunity growing bananas. Chiquita was growing the banana market and we felt that we could gain significant market share if we moved fast. But, having no money, we needed to be resourceful. So we traded chicken manure for banana keiki.

A little bit at a time we expanded, and after a bunch of transformations, we became the largest banana farm in the state. Then about 20 years ago we purchased 600 acres at Pepe‘ekeo and we got into hydroponic tomato farming.

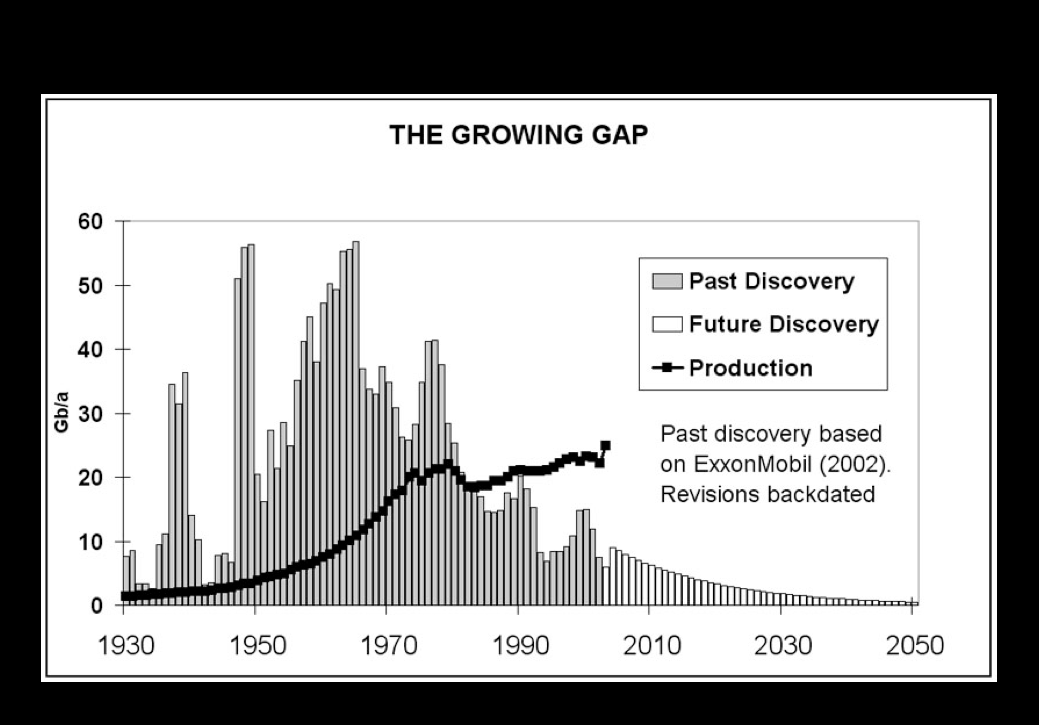

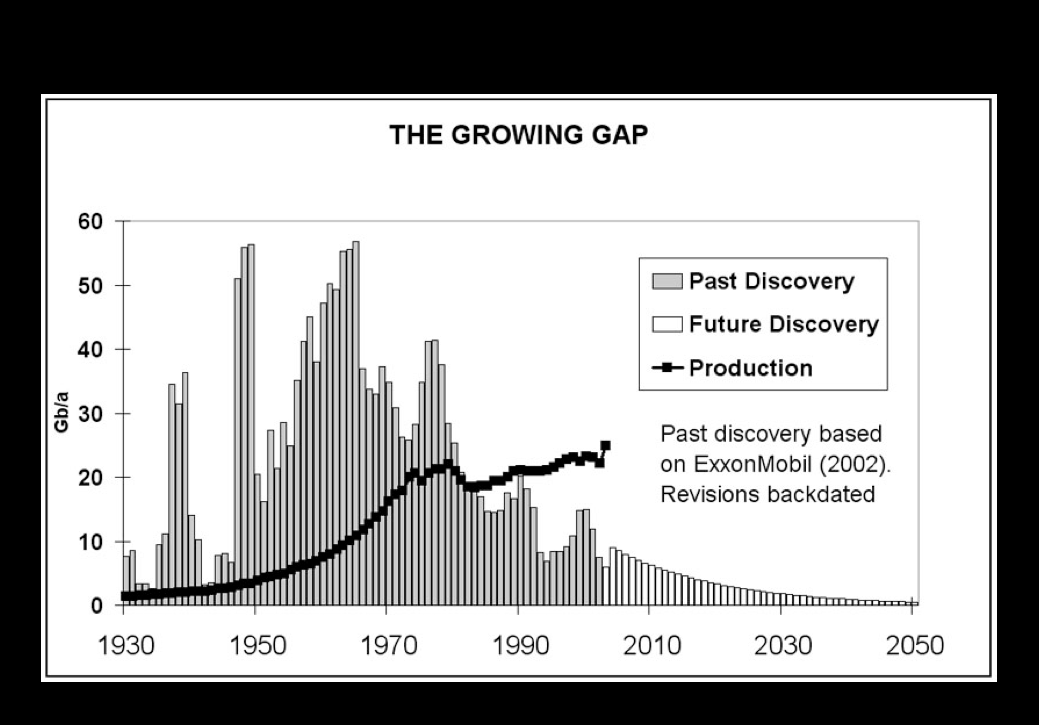

Approximately seven years ago, we noticed that our farm input costs were rising steadily, and I found out that it was related to rising oil prices. So in 2007, I went to the Association for the Study of Peak Oil (ASPO) conference to learn about oil. What I learned at that first ASPO conference was that the world had been using more oil than it was finding, and that it had been going on for a while.

In addition to using more than we were finding, it was also apparent that the natural decline rate of the world’s cumulative oil fields needed to be accounted for. The International Energy Association (IEA) estimates that this decline rate is around 5 percent annually. This amounts to a natural decline of 4 million gallons per year. We will need to find the equivalent of a Saudi Arabia every two and a half years. Clearly we are not doing that, and will never do that.

At the second ASPO conference I attended, in Denver in 2009, I learned that the concept of Energy Return on Investment (EROI) was becoming more and more relevant. It takes energy to get energy, and the net energy that results is what is available for society to use. In the 1930s, getting 100 barrels of oil out of the ground took the energy in one of those barrels. In 1970, it was 30 to 1 and now it is close to 10-1.

Tar sands is approximately 4 to 1, while some biofuels are a little more than 1 to 1. And, frequently, fossil fuel is used to make biofuels. That causes the break-even point to “recede into the horizon.”

But the EROI for geothermal appears to be around 10 to 1. And its cost won’t rise for 500,000 to a million years.

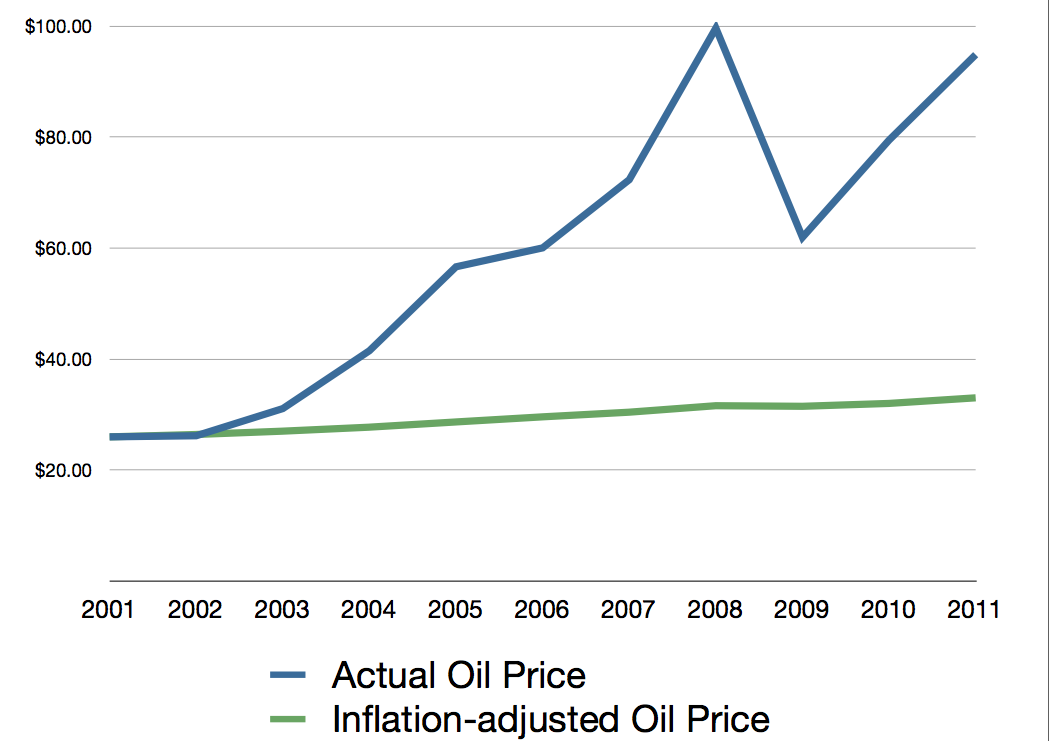

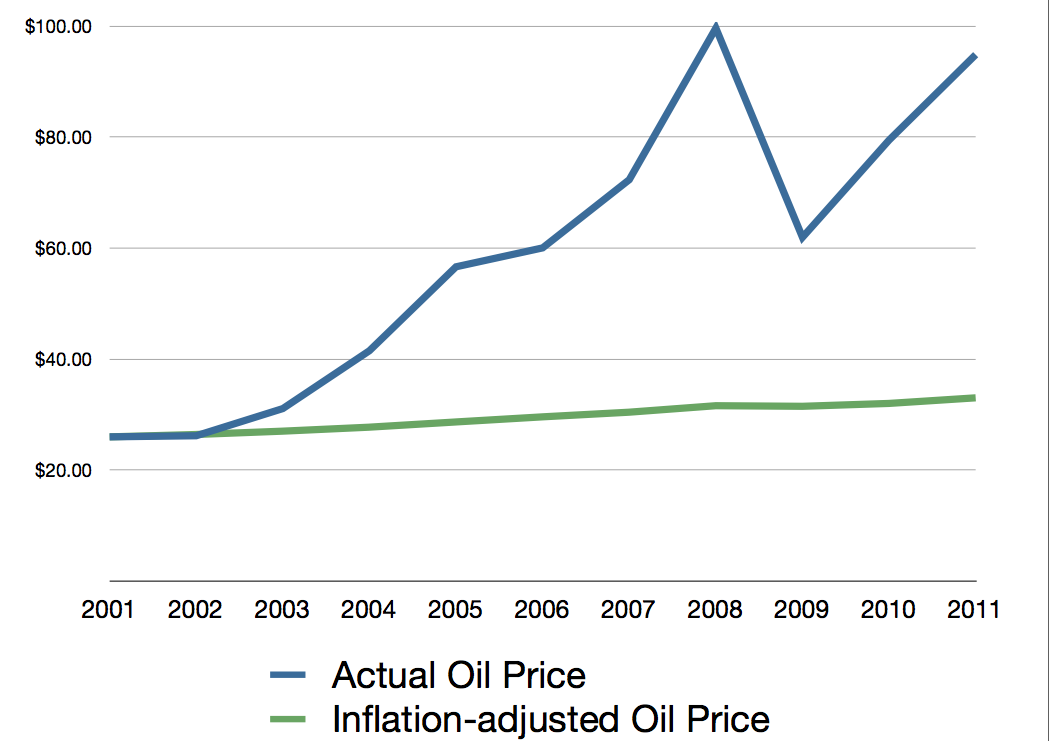

After the oil shocks of the early 1970s, the cost of oil per barrel was around the mid-$20 per barrel. That lasted for nearly 30 years.

In this graph above, one can see that oil would have cost around $35 per barrel in 2011, had inflation been the only influencer of oil price.

The cost of oil spiked in 2008, contributing to or causing the worst recession in history. In fact the last 10 recessions were related to spiking oil prices.

From late 2008 until mid-2009, the price of oil dropped as demand collapsed for a short time. But demand picked back up and the price of oil has climbed back to $100 per barrel – in a recession.

It is important to note that we in the U.S. use 26 barrels of oil per person per year, while in China each person uses only two barrels per person per year. Whereas we go into a recession when oil costs more than $100 per barrel, China keeps on growing. This is a zero sum game as we move per capita oil usage toward each other.

What might the consequences be as China and the U.S. meet toward the middle at 13 barrels of oil per person?

People are having a tough time right now due to rising energy-related costs. Two thirds of the economy is made up of consumer spending. If the consumer does not have money, he/she cannot spend.

How will we keep the lights on and avoid flickering lights? Eighty percent of electricity needs to be firm, steady power. The other 20 percent can be unsteady and intermittent, like wind and solar. So the largest amount of electricity produced needs to have firm power characteristics.

There are four main alternatives being discussed today.

- Oil is worrisome because oil prices will likely keep on rising.

- Biofuels is expensive and largely an unproven technology. The EPA changed its estimation of cellulosic biofuel in 2011 from 250 million gallons to just 6.5 million gallons because cellulosic biofuels were not ready for commercial production.

- Biomass or firewood is a proven technology. Burn firewood, boil water, make steam, turn a generator – that’s a proven technology. It is limited because you cannot keep on burning the trees; they must be replenished. And it’s not clear where that equilibrium point is. There are also other environmental issues.

- That leaves geothermal.

The chain of islands that have drifted over the Pacific hotspot extends all the way up to Alaska. This has been going on for over 85 million years.

It’s estimated that the Big Island, which is over the hot spot now, will be sitting atop that hot spot for 500,000 to a million more years.

Of all the various base power solutions, geothermal is most affordable. Right now it costs around 10 cents per Kilowatt hour to produce electricity using geothermal, while oil at $100 per barrel costs twice as much. The cost of geothermal-produced electricity will stay steady. Allowing for inflation, geothermal generated electricity will stay stable for 500,000 to a million years, while oil price will rise to unprecedented heights in the near future.

Geothermal is proven technology. The first plant in Italy is 100 years old. Iceland uses cheap hydro and geothermal. It uses cheap electricity to convert bauxite to aluminum and sells it competitively on the world market. With the resulting hard currency, it buys the food that it cannot grow.

Iceland is more energy- and food-secure than we are in Hawai‘i. Ormoc City in the Philippines, which has a population similar to the Big Island, produces 700MW of electricity with its geothermal resource, compared to our 30 MW. Ormoc City shares the excess with other islands in the Philippines.

Geothermal is environmentally benign. It is a closed loop system and has a small footprint. A 30 MW geothermal plant sits on maybe 100 acres, while a similarly sized biomass project might take up 10,000 acres.

In addition, geothermal can produce cheap H2 hydrogen when people are sleeping. It is done by running an electric current through water releasing hydrogen and oxygen gas. One can make NH3 ammonia by taking the hydrogen and combining it with nitrogen in the air. That ammonia can be used for agriculture. NH3 ammonia is a better carrier of hydrogen that H2 hydrogen.

The extra H atom makes NH3 one third more energy-dense than H2 hydrogen. It can be shipped at ambient temperature in the propane infrastructure.

The use of geothermal can put future generations in a position to win when the use of hydrogen becomes more mature.

If we use geothermal for most of our base power requirements for electric generation, as oil prices rise we will become more competitive to the rest of the world. And our standard of living will rise relative to the rest of the world.

Then, because two thirds of GDP is made up of consumer spending, our people will have jobs and we will not have to export our most precious of all our resources – our children.

In addition, people will have discretionary income and will be able to support local farmers, and that will help us ensure food security.