By Leslie Lang

Richard recently contributed tomato flowers for Take Our Daughters and Sons to Work Day at the Pacific Basin Agriculture Research Center (PBARC) in Hilo.

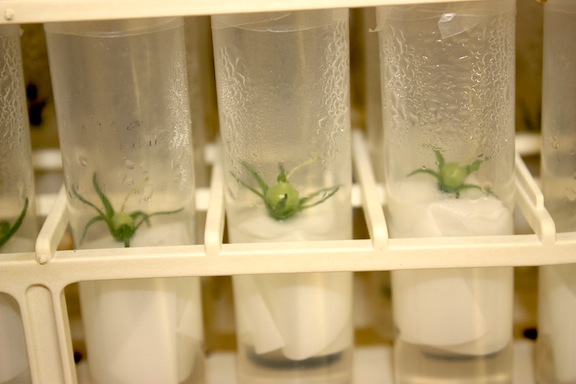

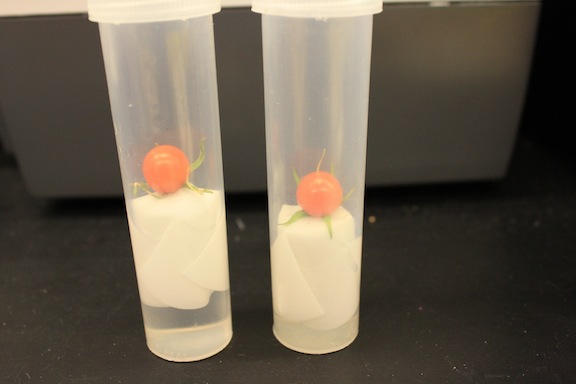

The cocktail tomato flowers were for a hands-on demo where kids learned about putting a tomato flower in sterile culture and growing their own tomato. They practiced removing flower petals with their fingers, and then saw how the scientists prepare the flowers under sterile conditions using forceps to remove the petals. The scientists put the flowers into a tissue culture and let the kids take them home and observe them developing into green tomatoes and then ripening.

It was the Ms. Foundation for Women (with support from foundation founder Gloria Steinem) who started “Take Our Daughters and Sons to Work Day” back in 1992; it started out as “Take Our Daughters to Work Day.” Sons were added in 2003. More than 37 million people participate every year at more than 3.5 million workplaces in the U.S., and there are more participants in over 200 other countries. Pretty impressive numbers!

From the Take Our Daughters and Sons to Work Foundation:

Exposing girls and boys to what a parent or mentor in their lives does during the work day is important, but showing them the value of their education, helping them discover the power and possibilities associated with a balanced work and family life, providing them an opportunity to share how they envision the future, and allowing them to begin steps toward their end goals in a hands-on and interactive environment is key to their achieving success.

PBARC participates once every three years, inviting employees to bring their children, nieces, nephews and grandchildren. Each child, too, can bring a friend.

Scientists set up displays and demos, usually hands-on, to demonstrate aspects of research and agriculture. Some of this year’s sessions had kids learning how to extract purple pigment from “red” cabbage, how to detect whether papaya seeds were genetically modified for ring spot virus, and drafting hibiscus cuttings. There was a short “genomic number cruncher” session, too.

“For the most part they are very engaged,” said research horticulturalist Tracie Matsumoto. “We keep the displays short, less than 30 minutes, and hands-on. One year we had a dead baby pig that we set up outside three weeks before the event, so the kids got to see the maggots and decaying carcass. That same entomologist who did that also set up a colony of sweet potato weevils one year, where the kids could put their arms in and let them crawl on their arms. Another year, we were extracting banana DNA and the kids got to take home DNA in a test tube.”

Because the facility recognizes that not every child wants to be a scientist, they also show the kids around all the other PBARC departments, so they see the various jobs that keep the facility going. They hear what the duties are for employees in administration, computer networking, janitorial and landscaping, payroll and purchasing. They learn that it takes more than just scientists to keep that operation going.

“We know students over the course of their lives are going to have multiple jobs and bosses and maybe careers, too, so we like to expand their expectations of what careers could be,” said Suzanne Sanxter, a biological laboratory technician and coordinator of the Daughters and Sons program.

Over the years, about 175 children between the ages of 7 and 18 have attended a PBARC Daughters and Sons event. This year there were 20 more, and all were asked to fill out surveys at the end of the day. PBARC must have really done something right, because each demo was listed as more than one students’ favorite, and reviews were glowing. A sampling:

How was your day at PBARC?

- Awesome and super fun, because we got to do a lot of things.

- It was the best and I wish there was more but I can’t wait for the next time I get to go.

- Amazing!

What did you like the best?

- I liked all of it, it was really fun the one that I liked the most was the tomatoe one and the calerpiler.

- All the subjects

- Going upstairs to see the wires.

What did you like the least?

- I loved all of it. All of them was really fun. I do not have any dislikes.

- Nothing

- Nothing

What experiment would you like to do next year?

- The experiment that I would want to do is the calipilier one, the tomatoe and the planting one in the patiow.

- Anything.

- Looking in the microscope.

What would you like to learn more about – plants or insects?

- What I would want to learn more is witch plant or fruit and inscect is the most endangered.

- How many years does a lemitoad (nematode ?!) stay alive.

- Insects.