Introducing Richard Ha’s New YouTube Channel

Response to News of Lawsuit

You may have seen the article on the front page of the Hawaii Tribune-Herald stating my wife June and I are among those being sued by the contractor building our medical cannabis growing site in Pepe‘ekeo.

It was a bit of a shock to see that on the front page of the paper before we were even served with the lawsuit or knew the details.

In this case, there is a dispute regarding services rendered. It’s not about choosing not to, or not being able to, pay the bill.

We pay our bills.

My wife June and I are only named in the suit because we own the land under the project, which we lease to Lau Ola.

When I was a small kid, my pop told me, “No mistake kindness for weakness.”

Why am I telling you this? Because what’s right is right.

Watch Hawaii News Now Next Wednesday

Hawaii News Now will interview me next Wednesday morning (April 19, 2017) for their Sunrise on the Road show.

They are going to be in Hilo for the Merrie Monarch Hula Festival and want to talk about agriculture on the Big Island and statewide, and also about our medical cannabis operation.

I believe it will air about 6:30 a.m. You can livestream it here.

Presenting Lau Ola’s Team, Progress, Obstacles

On January 25, we gave a presentation about Lau Ola to the Hawai‘i State Legislature’s medical marijuana legislative advisory committee. I thought I’d share it here, as well.

Aloha Everyone,

My name is Richard Ha, CEO of Lau Ola.

When I was asked if I would consider joining Lau Ola’s team, I said I would under three conditions:

- My workers would have first shot at the jobs.

- In addition to the required security, my neighbors would have external cameras monitoring traffic going up and down the road.

- My position would be a meaningful one, where I have influence over the direction Lau Ola goes.

Lau Ola is a triple bottom-line sustainable business. Nobel Prize-winning economist Joseph Stiglitz says that in order for a company to be sustainable in needs to be:

- environmentally sustainable

- economically sustainable

- socially sustainable

And that’s what Lau Ola is.

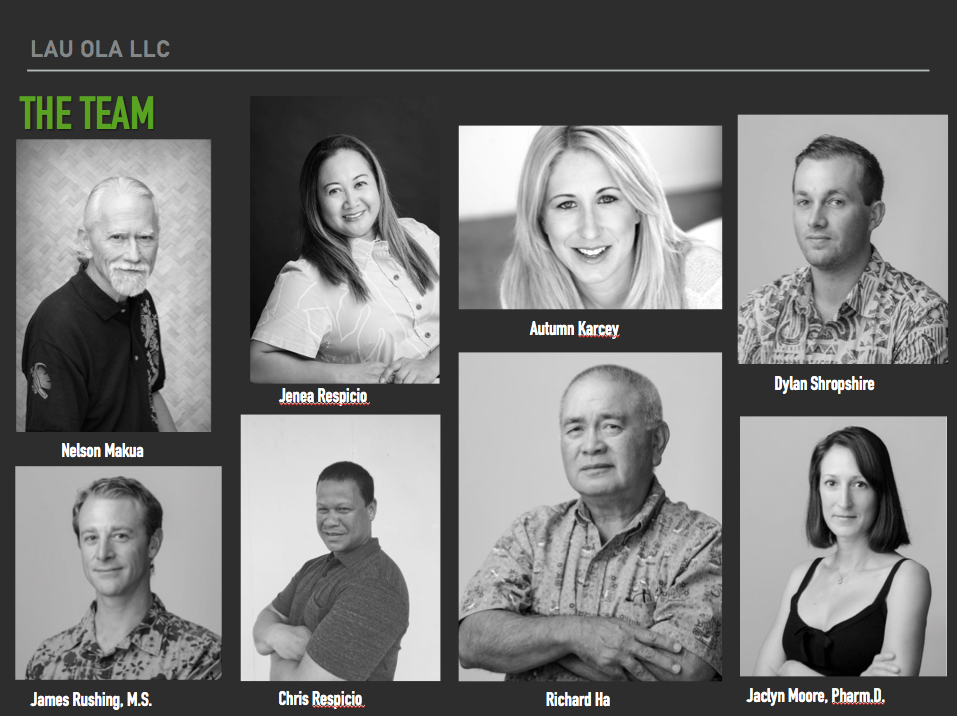

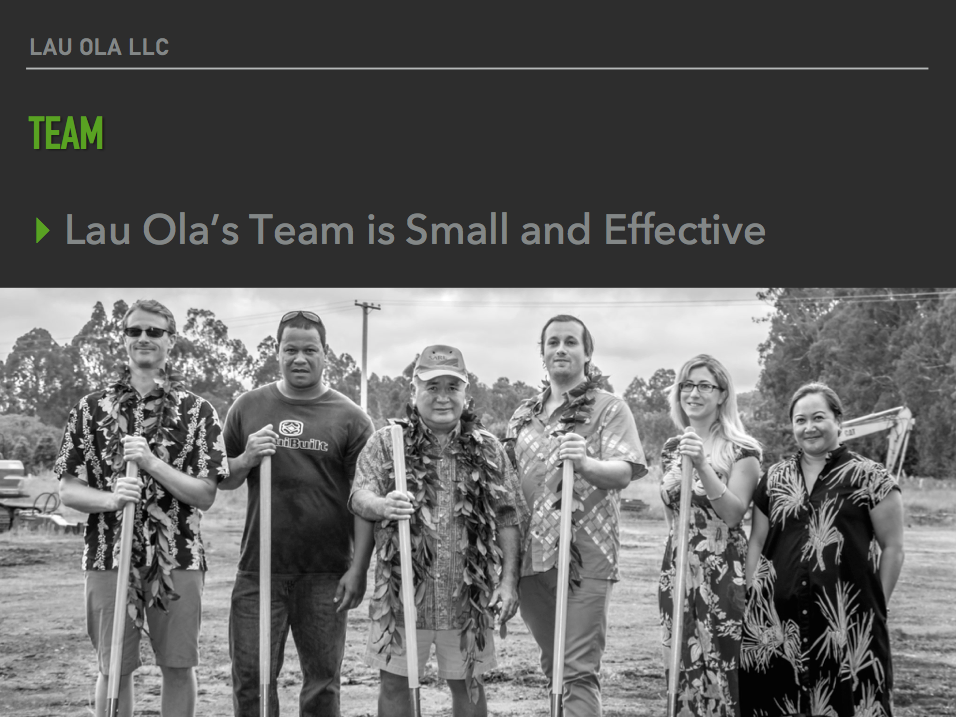

The four of us on the left have on-the-ground ag experience in Hawaii. Three have financial management skills. Chris and I farmed hydroponic tomato and vegetables for more than 10 years. We got 20 cents an ounce for high-end tomatoes and we had to fight all the insects and pests.

It’s not automatic that Lau Ola is going to make money. We take nothing for granted.

We are extremely proud of the three woman on our team. They are really good at what they do.

These are our people:

Jenea Respicio

- Administration

- Master of multi-tasking and organization

Chris Respicio

- Worked with me for 16 years

- We know and trust each other

James Rushing

- Master’s degree from UH Hilo

- Specializing in genetics and soil

Dylan Shropshire, COO

- Went to Hilo Intermediate and Hawaii Preparatory Academy

- Degree from Shidler College of Business

- Dual major in international business and finance

- Has worked in production agriculture since he was a baby

Autumn Karcey

- Born on Maui

- Built, designed and consulted on construction of Lau Ola-sized and bigger facilities in over 10 states and three countries

Nelson Makua

- Graphic designer

- Strong sense of place

- I’ve worked with Nelson for nearly 20 years

Jaclyn Moore, Pharm D (doctor of pharmacy)

- Community pharmacist licensed in Hawai‘i

- Experienced in implementing systems and procedures for compliance, security and patient safety

Our team feels good about where Lau Ola is heading.

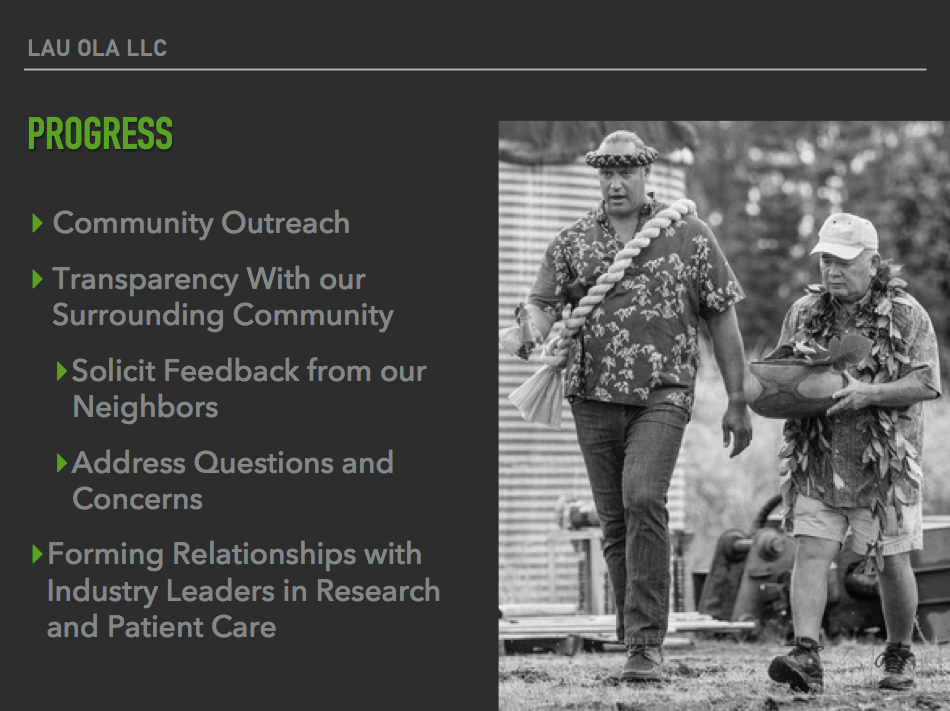

Our progress:

- We’ve had a neighborhood, informal Hibachi potluck get-together at the farm

- We are members of the community associations

- We have scheduled small group talk story sessions — with Rotarians, Chambers of Commerce, Kiwanis, cancer support groups and others

- All of the electricity generated by Hamakua Springs will be used (previously only half was used).

- We are very conscious about waste disposal

- And we have lots of other things going on, too

Lau Ola has also formed relationships with industry leaders in research and patient care. We are proud to align ourselves with these organizations.

To highlight that progress, let me introduce Tracy Ryan of Cannakids.

- Banking. Holding lots of cash is scary.

- Lab Standards. Quality testing before first harvest, so we have time to adjust our procedures.

- Education of doctors. Maybe as part of their continuing education credits.

Thank you.

Kamahele Family, Part 5 – What Uncle Sonny Kamahele Taught Me

Let me tell you something really interesting I learned from my Uncle Sonny Kamahele. He had 20 acres in Maku‘u, in Puna on the Big Island. There was a rare kipuka there with soil that was 10 feet deep, no rocks or anything. There was a spring in one corner of his property.

I was just out of college with an accounting degree and lots of ideas about business. So I looked at his land and wondered if he would lease me 10 acres to grow bananas. I scratched my chin and thought about how I could grow 35,000 pounds per acre on those 10 acres. Maybe 300,000 pounds a year if I took into account turn around space.

And yet on the other 10 acres, Uncle Sonny was making his living with just 10 or 20 hills of watermelons, with maybe four plants on each hill. People would come from miles around to buy his watermelons. It provided him with enough income to support himself and to send money to his wife and son in the Philippines.

Here’s the lesson I learned from him: It’s not about how big your farm is. Your business is successful if it supports your situation. I learned a lot from Uncle Sonny, but I think that’s the most important thing I learned from him.

That’s what I always look at when I visit a farm. Not how big it is, or how much money it makes, but how it operates, and whether it solves the problem it is trying to solve.

Here’s why I’m telling you this right now. We have a real energy problem looming. I think the situation with oil is very serious, and there are definitely going to be winners and losers in the world. We need to position ourselves to be winners, and it’s going to take all of us, big and small.

How are we going to feed Hawai‘i?

Every one of us is going to play a role in it – from the largest farmers to the small folks growing food in their backyard. Do you remember in the plantation camps, especially the Filipino camps, how the yards were always planted with food? Beans, eggplants, the whole thing. I don’t see it so much anymore, but we can do it again.

We are lucky on the Big Island. We’re not crowded and everybody has room to grow food. You know how you can tell we have plenty space? Everybody’s yard is too big to mow! We have the ability to do this.

It’s going to take all of us. It’s not just about any one of us, it’s about all of us, from the biggest to the smallest.

I’m lucky to have had my Uncle Sonny Kamahele to learn from when I was younger. I spent a lot of time with him and I got a real feeling for how he made decisions, which was old style.

Uncle Sonny Kamahele and lifestyle

His lifestyle was a real connection to the past, too. He kept his lawn and the whole area immaculate, practically manicured. He lived pretty close to the old ways with a lot of remnants from the past. His red and green house had stones from down the beach under the pillars, and lumber over the dirt floors. He built beds on those floors and then had five or six lauhala mats on the beds instead of mattresses; old style. There was a redwood water tank.

He listened to the County extension folks, and I learned from that, too – to pay attention to the people who know something.

But one of the most important things I learned was that your business, big or small, is a success if it supports your particular situation.

Maku‘u Stories, Part 1: My Kamahele Family in Maku’u

Maku‘u Stories, Part 2: Frank Kamahele

Maku‘u Stories, Part 3: Uncle Sonny Kamahele

Maku’u Stories, Part 4: Tutu Meleana & the Puhi

Kamahele Family, Part 4 – Tutu Meleana & the Puhi

Reposting a story I wrote several years back:

I just received a really interesting email about my Tutu Meleana. It was from my cousin Danny Labasan, and I’m copying it here with his permission:

I am the last son of Elizabeth Kamahele. I’m not sure if we met but we could have. I was so young way back then, I can’t remember who all of my cousins are. But I do remember once we went over to the chicken farm. I don’t know if Kimana or Kuuna was your dad. They were in Makuu all the time.

But how this writing came about is that I am doing some Kamahele family tree background. And while doing some Internet checks I ran across your articles via Hamakua Springs.

I just want to say that the stories you write, especially about Tutu, Uncle Sonny, the Maku‘u land, are so so so soo great. It’s like I am still there.

I wrote back that I know of him, though I don’t remember if we met either. His mom was Aunty Elizabeth, and I told Danny I have fond memories of her. I told him my dad was Kimana, which was a Hawaiianization of Kee Mun Ha, the name my dad’s Korean dad gave him.

Danny told me this great story about Tutu Meleana, who lived there at Maku‘u. Though Danny and I are near in age, Tutu was Danny’s grandmother and my great-grandmother.

The pond that you spoke of (Waikulani) where Tutu took you, and us as well, to fish as little kids – I have a story to tell about it. I will never forget it because it’s why I hate puhi (eel).

On one particular day, Tutu and my mom Elizabeth went to this pond. We swam and fished. Aunty Elizabeth caught lots of ‘opihi and Tutu caught some haukeuke. Then Tutu showed us how to clean the fish, the ‘opihi and haukeuke. We were on the rocks just feet from the ocean water. I was probably 6 years old. This will be hard to believe but a puhi came flying out of the water and grabbed hold of Tutu’s bicep. I will never forget seeing this snake-like creature attached to Tutu’s arm. I screamed until I hyperventilated.

But Tutu was so calm. She grabbed hold of the puhi’s head, pushed it against her arm and the mouth of the puhi opened up, and Tutu was able to remove the puhi from her arm. She cut the head off. Patched up her arm and we walked back to the house. An experience I will never forget. I still hate puhi.

My brother Allen, he was called Eloy during those days, would take us fishing in Kukuihaele where we lived and he would show us how Uncle Sonny and cousin Kalapo would catch puhi. Unreal.

Waikulani

What a story. Waikulani Pond is not exactly a pond. It was a place where the large waves outside would break on a protective ring of pahoehoe, and small swells would roll gently across what looks like a pond. One would have to jump from rock to rock to get to Waikulani. The bigger kids could do this, no problem.

The small kids would all go poke around in this tiny, protected cove, looking at ocean animals, and would sometimes see the dreaded puhi.

Great story, Danny. Thanks again.

See also:

Maku‘u Stories, Part 1: My Kamahele Family in Maku’u

Maku‘u Stories, Part 2: Frank Kamahele

Maku‘u Stories, Part 3: Uncle Sonny Kamahele

Precision Ag: MIT Students Use Drones to Analyze Soil Nutrient Load at Hamakua Springs

Richard was out with some Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) students conducting precision ag research at his farm when their drone swooped by and snapped this.

The undergraduate students are here with MIT’s Traveling Research Environmental Experiences (TREX) field research course. They are doing some environmental testing projects. At Hamakua Springs, their project is about “precision ag.”

‘Iolani School graduate Jon Kaneshiro is a graduate student in environmental engineering at MIT and a teaching assistant in the course. He explains they are using the drone to take remote images of the farm’s sweet potato fields. Then they process the images to analyze nutrient load.

“Using these high-definition, high-resolution drone images,” he says, “we can do some cool coding and processing to create a mosaic of a farm. It lets us see where potential low nutrient points are; where the plants aren’t doing well in the field. Sometimes if you just look at the field everything looks green. But if you use different image processing techniques, you can see which places are not doing as well as other places.”

Some large-scale farms might be using the technology, but Kaneshiro hasn’t heard of any Hawai‘i farmers using it.

It means a farmer doesn’t have to rely on satellite images, where resolution is poor. Clouds, too, can block satellite views. “We have big data from satellites,” he says, “but the resolution is oftentimes not enough to analyze your own smaller field.”

“Drones are pretty accessible,” he says. “They can cost a couple or a few thousand dollars. But if you hired a helicopter it’s going to be a thousand for only one ride. As compared to a drone, where you can go out with it every day. Or even multiple times in one day.”

The students are studying two different plots at Richard’s farm. One is 12-acres and the other is a four-acre plot of sweet potatoes.

Processing the Photos for Precision Ag

They process the raw images using applications and coding to isolate different types of bands, wavelengths, frequencies and the like. “We use software to code it,” says Kaneshiro, “but some of the students are really smart and doing it themselves, using coding and algorithms.”

“When you isolate the bands, you can see, visually, at a more intense level where there’s less growth in an area. You can see where the hot spots are.”

Once they find the “hot spots,” they test the soil at those places for pH and other nutrient levels.

“We can map the data onto the images and look at correlations and see what’s going on,” he says. “Why there are higher nutrients here, and where we need more nutrients.”

He says it’s a complex process but that it’s fun to see it all come together.

It’s merging remote sensing with precision ag, he explains. “The idea is that instead of a farmer dispersing large amounts of fertilizer over his whole field, maybe he can realize that, okay, that little 10 x 10 square in that corner over there needs more or less fertilizer, maybe because of a topographic feature.”

He says it’s a big divide. “We have the technology and the skills, but the divide between the farmers and the scientists is big.”

The students will be presenting about their project, as well as on sulfur dioxide sensors they have deployed in Pahala, at the Kona Science Cafe on Wednesday, January 25, 2017 at 5 p.m.. The public is welcome.

Kamahele Family, Part 3 – Uncle Sonny Kamahele

My Uncle Sonny Kamahele farmed at Maku‘u after some years in the Merchant Marines. His real name was Ulrich Kamahele (I have no idea where that name came from). He had a big personality.

One day, when I was walking with a couple of my buddies on Waianuenue Avenue near where Cronies is now, I heard someone call me. It was Uncle Sonny, and he was almost all the way up the block toward Kaikodo.

It’s hard to be rugged — even when you are in the 9th grade and smoking cigarettes — when your Uncle Sonny yells “Eh, Dicky Boy.” I cringed and looked around to see if any girls had heard him. He must have been in his 30s then.

I caught up with him again after I graduated from the University of Hawai‘i and returned home to run Pop’s chicken farm. When we decided to start growing bananas, we got lots of our banana keiki from Uncle Sonny. The Paradise Park subdivision had been built and so one could drive all the way down to Maku‘u. So we saw him quite frequently.

Uncle Sonny did not have electricity, running water or a telephone, but he had a transistor radio and a 1-foot stack of U.S. News and World Reports. He always got the current copy from the Pahoa post office. Though he lived a very simple life, he’d traveled all over the world with the Merchant Marines and he knew a lot more than one would think. He could talk about a myriad of subjects. I found his stories fascinating.

I visited him often and learned a lot about farming from him. A visit to Maku‘u would take hours, with most of that time spent listening to Uncle Sonny. I learned to be a good listener. He always talked in a loud voice and he waved his arms a lot. My wife June and my sister Lei told me that they would stay arms’ length from Uncle Sonny, walking backwards or in a big circle around the yard. They were careful to stay out of range of his swinging arms, so they wouldn’t be all bruised at the end of the visit.

Everyone knew Uncle Sonny for growing the sweetest watermelons. People would come from miles around to get his watermelons. He did not have to go out to sell them; they would all sell by word-of-mouth.

We spent a lot of time talking about farming watermelons. He used a backpack poison pump. Once he showed me how he knew that the amount of sticker/spreader in the mixture was effective. Although the rate was supposed to be something like ½-teaspoon per gallon, he always double-checked the mixture by sticking a piece of California Grass into it. Due to the fine hair on the grass, water normally runs off California grass, taking the herbicide with it. If the water spread on the leaf instead of running off it, the mixture was right.

What I learned from Sonny Kamahele

The message I learned: Use the book for the first approximation, and then confirm things on the ground. The word “grounded” does come to mind.

He told me that melon flies, an enemy of watermelon, rest under a leaf at the height of the midday sun. That was why he planted a few corn plants on the outside border of his watermelon patch. Sure enough, they were there. He was in tune with the behavior of the fruit fly. He would pull out his can of Raid and give them a short burst.

The standard solution would have been to spray the whole field. Uncle Sonny’s way was much more effective and very much cheaper.

Here’s how Uncle Sonny knew his watermelons were ready: When they reached the size of golf balls, he put a wooden stake with the date on it. Then he harvested the melons after a certain number of days went by.

It was so simple and so effective. It’s what led us to place a different colored ribbon on every banana bunch we bagged in a particular week. We harvested the bananas based on elapsed time—pretty much like Uncle Sonny did.

I learned from Uncle Sonny to use the “book” for general instructions. But not to rely on it exclusively.

Uncle Sonny broke things down to their essential components. He made his life simple, and yet he was very effective. I admired him very much.

See also:

Maku‘u Stories, Part 1: My Kamahele Family in Maku’u

Maku‘u Stories, Part 2: Frank Kamahele

There is a Pipeline for Hawaiian Astronomers

Sunday’s Hawaii Tribune-Herald had an article about Hawaiian astronomers testifying in the Thirty Meter Telescope contested case hearing last week.

From the article Astronomers Make Their Case:

Native Hawaiian astronomer Paul Coleman says the Thirty Meter Telescope would not just help unlock the mysteries of the universe, but also provide him a link to his ancestors.

Coleman, along with fellow astronomer Heather Kaluna, were the last of TIO International Observatory’s witnesses called in its ongoing contested case hearing this past week.

I first met Heather Kaluna back in 2006 or 2007 when I was a Keaholoa STEM advisor at the University of Hawai‘i at Hilo. The Keaholoa STEM program aims to “increase enrollment, support, and graduation rates of Native Hawaiian students at UH-Hilo in science & mathematics disciplines, and increase familiarity and the use of related technology.”

When I spoke to the college students back then, I told them about starting the Adopt-a-Class program at Keaukaha Elementary School. That program raised money to send students on field trips to places like ‘Imiloa Astronomy Center that they wouldn’t otherwise be able to take.

Heather was in the Keaholoa program. After I spoke, she came up and asked me how she could donate money to help the kids at Keaukaha. She was a “starving college student” herself. I knew she should be spending her money on putting herself through school, not worrying about the kids at Keaukaha. It stuck with me.

She studied astronomy at UH-Hilo and then UH-Manoa. Now she’s a postdoctoral fellow at the Hawaii Institute of Geophysics and Paleontology. I saw her recently when she and I, along with Barry Taniguchi, ended up on the selection committee for the new Institute for Astronomy (IfA) director.

There is a pipeline of Hawaiians coming up in astronomy. Paul Coleman was the first native Hawaiian astronomer. Then came Heather, and behind her is Mailani Neal.

Students that want to be Hawaiian astronomers

I attended the 2015 Office of Hawaiian Affairs (OHA) hearing when OHA voted to rescind its support of the TMT. Mailani, then a high school student at Hawaii Preparatory Academy, told trustees, in tears, that she wanted to go into astronomy. Now she is on the mainland getting her degree and she will be an astronomer.

And I know of at least one more person who may be in the Hawaiian astronomer pipeline. On one of my last tours of the banana farm, there was a girl from Kamehameha Schools. It was a couple years ago and I think she may have been in eighth grade. She hung close to me and I thought maybe she wanted to go into farming.

But afterward she came up and told me, in a soft voice, that she wanted to be an astronomer.

I really regret that I didn’t follow up and connect her with Heather and Mailani. That I didn’t tell them, “Look, here’s another girl coming up the pipeline.” After the fact, I tried to find out who that young girl was but I wasn’t successful.

I’m so conscious of young people in elementary school, middle school, high school. They have aspirations you don’t know about, and they need help when they need help.

It’s like the story I just told here about my cousin Frank Kamahele. He was 11 years old when he knew he was going to be an airplane pilot. He didn’t know how, but he knew he would be. And he was.

It still bothers me that I didn’t connect that young girl with the others already on the path, and I’d still like to. That was maybe two years ago. If anyone knows who she is, please let me know.